Modern scientific workflows often span tens or hundreds of thousands of tasks, forming deep DAGs (directed acyclic graphs) that handle large volumes of intermediate data. The large number of tasks primarily results from ever-growing experimental datasets and their partitioning into various data chunks. Each data chunk is applied to a subgraph to form a branch, and different branches typically have an identical graph structure. Collectively, these form a gigantic computing graph. This graph is then fed into a WMS (workflow management system) which manages task dependencies, distributes the tasks across a HPC (high performance computing) cluster, and retrieves outputs when they are available. Below is the general architecture of the data partitioning and workflow computation process.

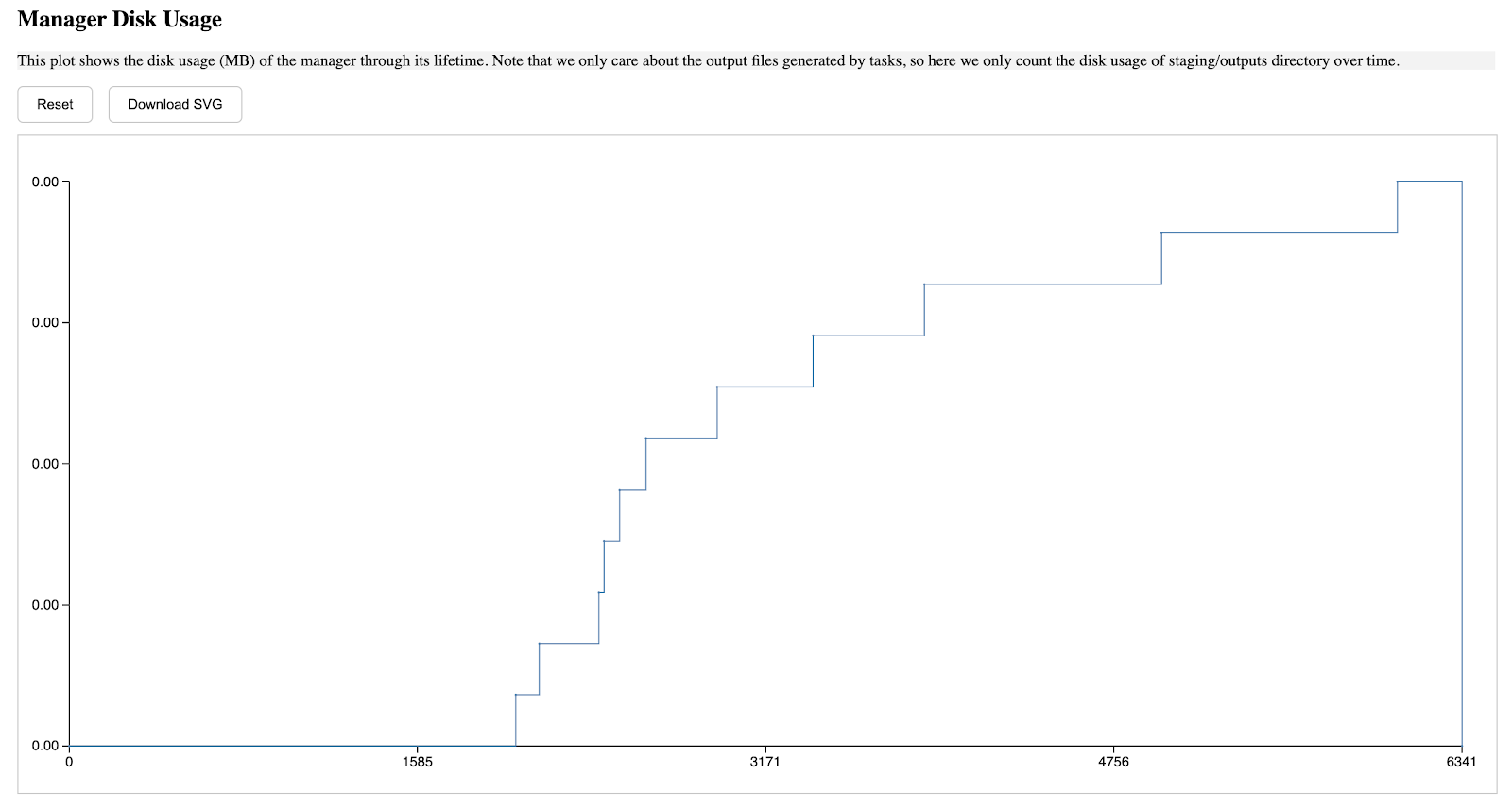

However, one of the challenges of using NLS is that the per-node storage capacity is limited. When requesting workers in the campus-held HPC cluster at the University of Notre Dame, the typical served worker has about 500 GB, which is much less than that of the PFS that is at the scale of hundreds of TB. Below is an example where intermediate data are generated over the course of computing the graph and are accumulated on individual workers.

On the one hand, we must have a way to promptly delete stale data that will not be needed in the future to free up space to avoid disk exhaustion on individual workers.

In TaskVine, we have the option to enable aggressive pruning for a workflow computation to save space. This allows us to promptly identify which files become stale and are safe to be detached from the system. Once recognized, the TaskVine manager directs all workers holding the file replicas to remove that replica from their own cache, and downstream tasks will no longer declare the pruned data as their inputs. This option is called aggressive pruning because no data redundancy is retained.

For example, the following figure shows the aggressive pruning for a given graph. File a is pruned when all the consumer tasks, namely Task 2, 3, and 4, have completed and their outputs have been updated. File b is pruned when the only consumer Task 6 has completed and the corresponding output File h has been created. At the time of T, four previously generated files have been pruned from the system, and the other four files are retained because there are some tasks needing them as inputs.

However, things become complicated when we consider worker failures at runtime. In an HPC environment, there is no guarantee that your allocated workers can sustain until your computation finishes, and worker failures or evictions are not rare. When workers exit at runtime, their carried data are lost as well. If pruning is too aggressive, a single worker eviction may force a long-chain recomputation.

Below is an example of this behavior. At the time of T, Worker 2 is suddenly evicted. Task 9 and Task 10 are interrupted and collected back to the manager. Meanwhile, the intermediates stored on Worker 2, namely File e, f, g, and h, are also lost. Some of them have additional replicas on other workers, but File f does not, so it is completely lost because of the eviction. Due to the data loss, Task 9 cannot run until its input File f is recreated. To regenerate File f, we must rerun Task 7. However, Task 7 cannot run because its input File c has been pruned. Thus, we are forced to work all the way back to the top of the graph to regenerate the lost file. Worse yet, we may ultimately end up having the longest path in the graph recomputed, prolonging the graph makespan and undermining the scientific outcome.

So, to reserve certain redundancies to minimize recomputation in response to worker failures, TaskVine provides the option to tune the depth of ancestors for each file before it can be pruned.

In the implementation, pruning is triggered at the moment a task finishes, when its outputs are checked for eligibility to be discarded. Each file carries a pruning depth parameter that specifies how many generations of consumer tasks must finish before the file can be pruned. Depth-1 pruning is equivalent to aggressive pruning, while depth-k pruning (k is greater than or equal to 2) retains the file until every output of its consumer tasks has itself satisfied the depth-(k-1) criterion. Formally, the pruning time is defined as: P(f) equals the minimum of P-sub-k(g) for all g that are outputs of f's consumers.

where Cons(F) denotes the consumer tasks of file F and Out(T) the outputs of task T. This recursive evaluation avoids expensive global scans by localizing pruning decisions to task completion events, with overhead proportional only to the chosen depth. As k increases, more ancestor files are preserved, providing redundancy and shrinking recovery sub-DAGs, whereas smaller k values reduce storage usage at the expense of higher recovery cost.

The figure below shows the improvement after applying depth-2 pruning, where we are able to preserve more data redundancy at runtime. At time T, Worker 2 is evicted, File f is completely lost, and we must recover it in order to rerun Task 9. Thanks to depth-2 pruning, File c can be found on another worker, so we can restart from there. This way, we avoid the need to go all the way back, though at the risk of consuming more local storage on individual workers.

Depth-aware pruning can work in conjunction with two other fault tolerance mechanisms in TaskVine: peer replication, in which every intermediate file is replicated across multiple workers, and checkpointing, in which a portion of intermediates are written into the PFS for persistent storage. Subsequent articles will cover these topics to help readers better understand the underlying tradeoffs and know how to select the appropriate parameters to suit their own needs.

TaskVine users can explore the manual to see how to adjust these parameters to suit their needs for the tradeoff between storage efficiency and fault tolerance. For depth-aware pruning, we recommend using aggressive pruning (depth-1 pruning) as the general and default setting to save storage space to the largest extent, and increase the depth parameter when worker failures are not uncommon and additional data redundancy is needed.